The speaker of Ovid's "Contrite Lover" elegy in

Amores reflects on a quarrel in which he struck his lover. Full of remorse, he asks this of his own hands: "What have I to do with you, servants of murder and crime?" (

Amores I, 7, 27). As Hermann Fränkel puts it, the speaker "feels estranged from his own self of a moment before. His identity is broken up...." (Fränkel,

Ovid: A poet Between Two Worlds, pp. 20-21) The great classical scholar considers Ovid's representation of inner conflict a historic literary achievement:

[I]t was an unheard-of novelty for the ancients that a person should no longer feel securely identical with his own self.... There is no sign of a previous emergence of these possibilities; Ovid took them for granted and used them freely in his poetry.... [W]ith the self losing its solid unity and being able half to detach itself from its bearer, a fundamental shift had taken place in the history of the human mind. Frankel, p. 21

Before Ovid came along, Plato and other ancient philosophers had postulated a self divided by competing faculties of passion and reason. But who had ever represented the subjective

experience of these internal divisions with Ovid's level of modern realism? Even among later poets, who but Shakespeare has represented our divided consciousness so well as Ovid?

Indeed, in Ovid's representations of mental life, schisms of identity and clashes between wishes and realities precipitate solutions where a troubling aspect of self or world is rejected from consciousness. "Time and again," Fränkel writes of the

Amores, "we find Ovid bent on concealing from his own eyes a disagreeable fact; but he also sees to it that the cloak is transparent." (Fränkel, p. 31) In the

Heroides, one of Ovid's heroines, Phyllis, attests to the same phenomenon: "one is slow to give credence to that which brings pain.... Often I lied to myself...." (quoted in Fränkel, p. 42)

True, there are antecedents to Ovid's notion of denial, too. Consider his telling of the famous story of Jupiter and Io, first in the

Heroides and again in the

Metamorphoses. Ovid seems deliberately to echo Sophocles. "What is the reason for your flight?" Ovid writes of the nymph Io in the

Heroides. (To hide his affair from Juno, Jupiter has turned Io into a cow and Io goes mad trying to run from her new form when she cannot.) "You will never escape from your own face.... You are the same who both pursues and flees. It is you who lead yourself, and you go where you lead." (quoted in Fränkel p. 79) Whether or not Ovid intended it, the lines certainly call to mind Teiresias's stunning words to Oedipus in

Oedipus Rex: "I say you are the murderer of the king whose murderer you seek."

Ovid, however, accomplishes with his fantastic tales what Sophocles did not attempt: he converts the ancient wisdom written on the Temple of Apollo at Delphi--

gnothi sauton in the original Greek (

nosce te ipsum in Latin, "know thyself" in English)--into psychological realism that not only depicts inner conflict and denial in personal terms, but actually examines what Freud later called defense mechanisms.

That is to say, not all transformation in

Metamorphoses is supernatural. In many cases Ovid in fact dispenses with the fantastical metamorphoses and depicts in straight realist terms an emotion being actively revised or altered by another. For example in Book II Phaethon asks his father Apollo whether Clymene (Phaethon's mother) lied when she said Apollo was his father. His exact words are

nec falsa Clymene culpam sub imagine celat (

Metamorphoses, II, 37), "if Clymene is not hiding her shame beneath an unreal pretence." Here Ovid makes the pattern of pain and emotional flight more intricate, more subtle: the particular pain in this case is

shame; the particular means of evasion is

hiding.

At times Ovid upstages Freud to the degree that he uses Freudian terms like "repression" and "transference" in connection with pretty much the same phenomena Freud sought to describe.

erebuit Phaethon iramque pudore repressit, "Phaethon blushed and repressed his anger in shame." (I, 755)

Iovis coniunx ... a Tyria collectum paelice transfert in generis socios odium, "the wife of Jove had now transferred her anger from her Tyrian rival to those who shared her blood." (II, 256-259)

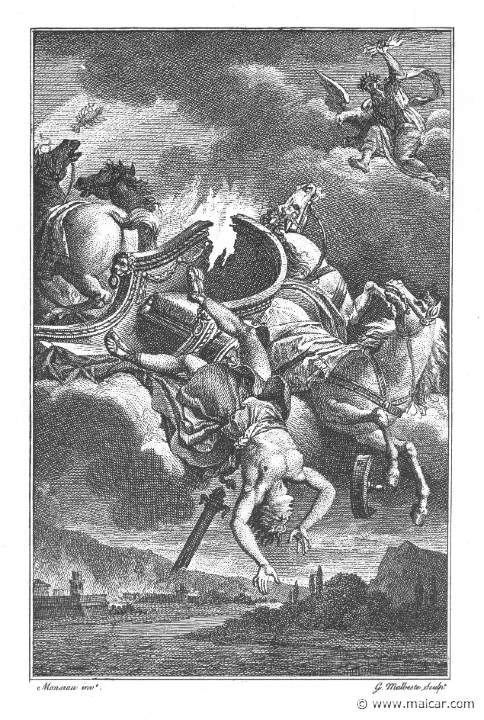

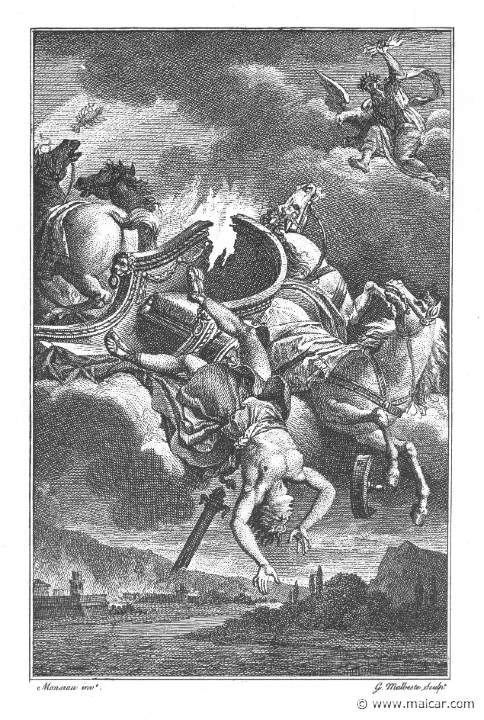

The Phaethon episode in Book II, one of the best in the

Metamorphoses, tracks Apollo's changing emotions in sequence like a psychoanalyst would. After his son Phaethon's death, Ovid tells us,

lucemque odit seque ipse diemque datque animum in luctus et luctibus adicit iram officiumque negat mundo, or "He hates himself and the light of day, gives over his soul to grief, to grief adds rage, and refuses to do service to the world." (

Metamorphoses, II, 383-385)

After Jupiter goads Apollo into climbing back into the chariot to light the world, Ovid writes:

Phoebus equos stimuloque dolens et verbere saevit (saevit enim) natumque obiectat et inputat illis, "in his grief Phoebus savagely plies the horses with lash and goad (so savagely), reproaching and taxing them with the death of his son." (II, 399-400) It's true that the horses were an instrument in Phaethon's demise, but Apollo knows that they are innocent beasts, that the fault lies most of all with Phaethon himself and with Jupiter, who threw the thunderbolt that killed him--and who, after making a brief apology, had the audacity to threaten Apollo if he didn't resume his duties. Ovid implies quite unambiguously that Apollo whips the horses in Jupiter's place, in Phaethon's place, in his own place.

When Jupiter rapes Callisto, one of Diana's maidens, Ovid writes,

huic odio nemus est et conscia silva "She loathed the forest and the woods that knew her secret." (II, 338) She seems to hate the woods in place of Jupiter (again), because Jupiter is too terrible to attack directly. Perhaps Callisto also hates the woods in place of her own guilt. Ovid continues,

quam difficile est crimen non prodere vultu! "How hard it is not to betray guilt in the face!" (II, 447) Freud teaches us that guilt is a major, if not

the major, stimulus to repression. Guilt causes people to hide emotions from themselves and from others. More often than not,

transformation of ideas and affects does the hiding. Shakespeare knew this before Freud. And Ovid evidently knew it before either one of his great intellectual heirs, as transformative defense mechanisms of displacement and identification abound in his

Metamorphoses. I found it most interesting that Ovid describes Nyctimene, a woman who slept with her father and was punished by turning into a bird, as being

conscia culpae--literally "conscious of her guilt." (II, 593) It implies she might also have been

unconscious of it. Ovid would have had little trouble understanding Shak and Freud, and it's obvious that "Ovid's amazing candor" (Fränkel, p. 58) imparted much psychological wisdom to later ages.

Darrel Abel was born in Lost Nation, Iowa in 1911. He taught American literature at Purdue for many years, and at some point, working from the obscurity of Lisbon Falls, Maine, he produced a rather lovely little paper called "Robert Frost's 'Second-Highest Heaven'," which he published in 1980. The paper's title refers to a piece of Frost's prose on Ralph Waldo Emerson. Frost wrote:

Darrel Abel was born in Lost Nation, Iowa in 1911. He taught American literature at Purdue for many years, and at some point, working from the obscurity of Lisbon Falls, Maine, he produced a rather lovely little paper called "Robert Frost's 'Second-Highest Heaven'," which he published in 1980. The paper's title refers to a piece of Frost's prose on Ralph Waldo Emerson. Frost wrote:

did the same and deduced that if the universe has expanded, it must once have been compact. The idea was not that the matter of the universe exploded like shrapnel from a bomb (one reason "Big Bang" is an imperfect name), but rather that the empty space of the universe itself was once compact and ever since has been stretching out like silly putty.

did the same and deduced that if the universe has expanded, it must once have been compact. The idea was not that the matter of the universe exploded like shrapnel from a bomb (one reason "Big Bang" is an imperfect name), but rather that the empty space of the universe itself was once compact and ever since has been stretching out like silly putty.  The speaker of Ovid's "Contrite Lover" elegy in Amores reflects on a quarrel in which he struck his lover. Full of remorse, he asks this of his own hands: "What have I to do with you, servants of murder and crime?" (Amores I, 7, 27). As Hermann Fränkel puts it, the speaker "feels estranged from his own self of a moment before. His identity is broken up...." (Fränkel, Ovid: A poet Between Two Worlds, pp. 20-21) The great classical scholar considers Ovid's representation of inner conflict a historic literary achievement:

The speaker of Ovid's "Contrite Lover" elegy in Amores reflects on a quarrel in which he struck his lover. Full of remorse, he asks this of his own hands: "What have I to do with you, servants of murder and crime?" (Amores I, 7, 27). As Hermann Fränkel puts it, the speaker "feels estranged from his own self of a moment before. His identity is broken up...." (Fränkel, Ovid: A poet Between Two Worlds, pp. 20-21) The great classical scholar considers Ovid's representation of inner conflict a historic literary achievement:

Ovid was "revered among Elizabethan pedagogues" according to R.W. Maslen (Shakespeare's Ovid, p. 17). It sounds like a terrible fate, to be revered by a pedagogue, let alone a bunch of Elizabethan ones. I don't know for certain what happens if one reveres you, but if one kisses you, I think you get warts. Or am I thinking of frogs? In any case, like many Elizabethans, Shakespeare purportedly encountered Ovid in grammar school. The Roman poet seems to have left an impression on the Stratford boy who lived an age and a half later.

The Metamorphoses in fact figures into Shak's early tragedy Titus Andronicus in an unusual way for a Shakespeare play: "In perhaps the most self-consciously literary moment in all Shakespeare," as Jonathan Bate puts it (Golding trans. frontmatter, p. xliv), a physical copy of Ovid's book appears onstage. Young Lucius is reading it and his aunt Lavinia, who like Philomela in the Metamorphoses has had her tongue cut out, tries to communicate her own story by turning the pages to the story of Philomela and Procne. Philomela had to weave a tapestry to communicate, but Lavinia's attackers had also chopped her hands off, so in place of weaving a tapestry, she uses Ovid's story about the tapestry!!!

Shak famously ate up source material both high and low and incorporated it all into his works, but I find it striking that the Metamorphoses alone (?) turns up in this undigested form--whole, as it were, with its binding still on it like some piece of literary roughage that even Shakespeare's omnivorous guts could not fully break down. Titus Andronicus does not incorporate Ovid so much as embrace him like a peach pit in the belly of a gull, or quartz in the belly of an oyster.

With Ovid in his craw, Shak made quite a few pearls. Ovid provided Shakespeare with source material that turns up in Titus Andronicus, A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Tempest, and many other plays, and in fact, according to Bate (p. xlii), "[s]cholars have calculated that about ninety percent of Shakespeare's allusions to classical mythology refer to stories included in this epic compendium of tales [Metamorphoses]." More importantly, however, Ovid provided to Shakespeare not only material but some of his most important themes and methods. It looks to me like Ovid (and his Greek and Roman antecedents), not Montaigne or Shakespeare, is more nearly the inventor of the inward-looking soliloquy. First, Ovid brilliantly portrayed the mind talking to itself in his Heroides, using what Hermann Fränkel calls "thought letters." (Ovid: A Poet Between Two Worlds, p. 37) Then he developed that technique into totally "Shakespearean" inner debates in the Metamorphoses. Bate again:

Ovid was "revered among Elizabethan pedagogues" according to R.W. Maslen (Shakespeare's Ovid, p. 17). It sounds like a terrible fate, to be revered by a pedagogue, let alone a bunch of Elizabethan ones. I don't know for certain what happens if one reveres you, but if one kisses you, I think you get warts. Or am I thinking of frogs? In any case, like many Elizabethans, Shakespeare purportedly encountered Ovid in grammar school. The Roman poet seems to have left an impression on the Stratford boy who lived an age and a half later.

The Metamorphoses in fact figures into Shak's early tragedy Titus Andronicus in an unusual way for a Shakespeare play: "In perhaps the most self-consciously literary moment in all Shakespeare," as Jonathan Bate puts it (Golding trans. frontmatter, p. xliv), a physical copy of Ovid's book appears onstage. Young Lucius is reading it and his aunt Lavinia, who like Philomela in the Metamorphoses has had her tongue cut out, tries to communicate her own story by turning the pages to the story of Philomela and Procne. Philomela had to weave a tapestry to communicate, but Lavinia's attackers had also chopped her hands off, so in place of weaving a tapestry, she uses Ovid's story about the tapestry!!!

Shak famously ate up source material both high and low and incorporated it all into his works, but I find it striking that the Metamorphoses alone (?) turns up in this undigested form--whole, as it were, with its binding still on it like some piece of literary roughage that even Shakespeare's omnivorous guts could not fully break down. Titus Andronicus does not incorporate Ovid so much as embrace him like a peach pit in the belly of a gull, or quartz in the belly of an oyster.

With Ovid in his craw, Shak made quite a few pearls. Ovid provided Shakespeare with source material that turns up in Titus Andronicus, A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Tempest, and many other plays, and in fact, according to Bate (p. xlii), "[s]cholars have calculated that about ninety percent of Shakespeare's allusions to classical mythology refer to stories included in this epic compendium of tales [Metamorphoses]." More importantly, however, Ovid provided to Shakespeare not only material but some of his most important themes and methods. It looks to me like Ovid (and his Greek and Roman antecedents), not Montaigne or Shakespeare, is more nearly the inventor of the inward-looking soliloquy. First, Ovid brilliantly portrayed the mind talking to itself in his Heroides, using what Hermann Fränkel calls "thought letters." (Ovid: A Poet Between Two Worlds, p. 37) Then he developed that technique into totally "Shakespearean" inner debates in the Metamorphoses. Bate again:

Book XV is more than the coda to the Metamorphoses. It too is a transformation. Here at the end of Ovid's poem, he turns from fable to the real historical figure of Julius Caesar so that mythology itself metamorphoses into history. In this same Book, Ovid invites Pythagoras into the narrative as spokesman for the new age, offering a vision of the world that seems to be shedding itself of the old mystic fog even as we read. As Simon Singh tells us in his book on the Big Bang (Big Bang, p. 7), Pythagoras helped initiate the "new rationalist movement" that dawned on the world in the 500s B.C.E. And Ovid shows he's quite alert to the transition into modernity which began with the Greek Enlightenment and continued with the Roman one of his own day; such an awareness explains the sophistication with which Ovid re-invented the old fables as realist studies of the intricacies of emotion and behavior.

Book XV is more than the coda to the Metamorphoses. It too is a transformation. Here at the end of Ovid's poem, he turns from fable to the real historical figure of Julius Caesar so that mythology itself metamorphoses into history. In this same Book, Ovid invites Pythagoras into the narrative as spokesman for the new age, offering a vision of the world that seems to be shedding itself of the old mystic fog even as we read. As Simon Singh tells us in his book on the Big Bang (Big Bang, p. 7), Pythagoras helped initiate the "new rationalist movement" that dawned on the world in the 500s B.C.E. And Ovid shows he's quite alert to the transition into modernity which began with the Greek Enlightenment and continued with the Roman one of his own day; such an awareness explains the sophistication with which Ovid re-invented the old fables as realist studies of the intricacies of emotion and behavior.

The middle of summer -- July -- if you walk west on Montague Street toward the harbor at around 6:30 in the evening, carrying your bag of black plums, the water is a gigantic cauldron of fire that sets upon every head a backlighting halo. It's like something out of On Golden Pond except that it smells like garbage and there's dogshit all over the sidewalk. You see more fire dripping from a top floor air conditioner and exploding on the awning of an Italian restaurant like ore dripping from a smelter. You see girls with bare arms and bare legs. Up, down, and sideways, you see boobs boobs boobs.

Ah, summer! "For there is no hardier time than this," Ovid writes in his Metamorphoses, "none more abounding in rich, warm life." Bk XV, ll. 207-208.

In August you drive to the beach with the windows down and the "where do we go now" part of "Sweet Child o' Mine" breaking down on the car stereo at an almost painful volume, and you have a vanilla ice cream cone in each hand and are driving with your knee (not really, I can't digest milk, but you get the idea), and you're watching the girls with their bikinis and their cover-ups, and you're thinking to yourself, "If Norman Mailer was here, I would karate chop him in the neck" and you don't even pity Slash for being less of a bad-ass than you are. And your boys are in the back seat in their bare feet, without their seatbelts on and you don't even care.

Or maybe you ride a bike and you have no urge to karate chop Norman Mailer. Anyway, I am more bad-ass than Slash because, in addition to sometimes not forcing my shoeless kids into their seatbelts, I read Ovid's Metamorphoses this summer, as well as Hermann Fränkel's magnificent Sather Lectures on Ovid, given at Berkeley 65 or 70 years ago.

Frankel calls Ovid "a poet between two worlds," because in many ways he is the first truly modern writer--a writer with an enlightened, scientific, expressly psychological worldview--even more so than his great predecessor Virgil:

The middle of summer -- July -- if you walk west on Montague Street toward the harbor at around 6:30 in the evening, carrying your bag of black plums, the water is a gigantic cauldron of fire that sets upon every head a backlighting halo. It's like something out of On Golden Pond except that it smells like garbage and there's dogshit all over the sidewalk. You see more fire dripping from a top floor air conditioner and exploding on the awning of an Italian restaurant like ore dripping from a smelter. You see girls with bare arms and bare legs. Up, down, and sideways, you see boobs boobs boobs.

Ah, summer! "For there is no hardier time than this," Ovid writes in his Metamorphoses, "none more abounding in rich, warm life." Bk XV, ll. 207-208.

In August you drive to the beach with the windows down and the "where do we go now" part of "Sweet Child o' Mine" breaking down on the car stereo at an almost painful volume, and you have a vanilla ice cream cone in each hand and are driving with your knee (not really, I can't digest milk, but you get the idea), and you're watching the girls with their bikinis and their cover-ups, and you're thinking to yourself, "If Norman Mailer was here, I would karate chop him in the neck" and you don't even pity Slash for being less of a bad-ass than you are. And your boys are in the back seat in their bare feet, without their seatbelts on and you don't even care.

Or maybe you ride a bike and you have no urge to karate chop Norman Mailer. Anyway, I am more bad-ass than Slash because, in addition to sometimes not forcing my shoeless kids into their seatbelts, I read Ovid's Metamorphoses this summer, as well as Hermann Fränkel's magnificent Sather Lectures on Ovid, given at Berkeley 65 or 70 years ago.

Frankel calls Ovid "a poet between two worlds," because in many ways he is the first truly modern writer--a writer with an enlightened, scientific, expressly psychological worldview--even more so than his great predecessor Virgil: